Issue 83: Binge Eating Disorder and Bulimia Nervosa

About this resource

Binge eating disorder and bulimia nervosa snapshot

Q&A with Eating Disorders Victoria

Q&A with Western Sydney University’s Dr Deb Mitchison

Q&A with Inside Out Institute’s Dr Jane Miskovic-Wheatley, Sarah Barakat, and Emma Bryant

Guide to binge eating disorder and bulimia treatment options

References and further reading

Editor’s Note

“We were hearing from more and more Victorians living with binge eating disorder who felt like their experience was considered less important than other eating disorders.” Eating Disorders Foundation of Victoria (EDV).

Most people have a stereotyped image of an eating disorder, but what they may not know is that the eating disorder most commonly affecting people globally is binge eating disorder (BED), which affects men almost equally, followed by bulimia nervosa (BN) (Santomauro et al., 2021). In this issue we will explore the characteristics and complex psychological and sociocultural factors behind binge eating disorder and bulimia nervosa and barriers to treatment such as shame, stigma and lack of knowledge. We reached out to experts to inform our readers about the latest studies and initiatives taking place in Australia and the hopes of people with lived experience, clinicians, and researchers working in this space to improve outcomes. Read more here.

“Our community experiencing binge eating disorder wants to experience accessible and respectful care, and they are entitled to that.” Read our Q&A with EDV’s Breanna Guterres about the lived experience-led initiative ‘Our Vision for BED’ here.

“We have less research conducted on diagnoses other than anorexia nervosa, on genders other than female, on body shapes other than thin, and on ethnic and racial groups other than white/Caucasian.” Western Sydney University researcher and 2022 ANZAED Conference co-convener Dr Deb Mitchison discusses current binge eating disorder and bulimia nervosa issues and research findings here.

“We need to advocate for less stigma and more community awareness, more screening in primary care settings, more focus on clinical engagement and more provision of evidence-based treatment.” Inside Out Institute's Dr Jane Miskovic-Wheatley, Sarah Barakat, and Emma Bryant write about how new research and tools for screening and treating binge eating disorder can help clinicians here.

Read about binge eating disorder and bulimia nervosa treatment options here and find links to recent research on these topics here.

In this issue NEDC also updates you about our latest eating disorder fact sheets, and new resources for Primary Health Networks (PHNs) and service providers. You can access new resources below and read about them here:

Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD) fact sheet

Quick Reference Guide for Primary Care Professionals and Service Providers

Eating disorders: Identification and response

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy Guided Self Help (CBT-GSH) fact sheet

Learn about upcoming training and events taking place in November and December, including a Western Australia Eating Disorders Outreach and Consultation Service (WAEDOCS) masterclass for dietitians focusing on binge eating disorder here.

The NEDC is about collaboration and connection. Please share this eBulletin with colleagues and friends. Your input and your voice matter to us. Contact us at info@nedc.com.au You can also participate through membership to the NEDC – join us here.

Binge eating disorder and bulimia snapshot

Often regarded as “hidden” eating disorders, the numbers of people experiencing binge eating disorder and bulimia nervosa are in fact climbing. A recent study found a 66% increase in binge eating symptomatology associated with the COVID-19 pandemic (Miskovic-Wheatley, 2022). It is crucial that we better understand the complex elements underlying risk factors for these eating disorders and what can be done to better recognise, assess and support people to access treatment.

Binge eating disorder is characterised by a sense of loss of control, eating a large amount of food in a short amount of time, and feelings of guilt, shame and distress. Bulimia nervosa shares these characteristics but people living with bulimia also engage in ‘compensatory behaviours’, or behaviours intended to remove food from the body or ‘make up for’ the calories consumed following a binge eating period.

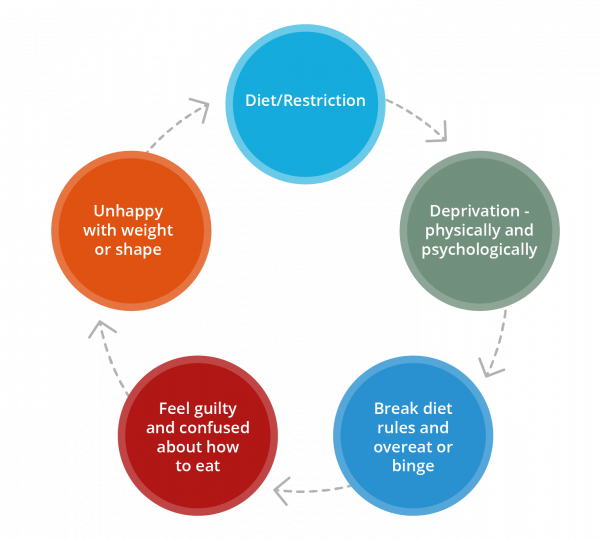

Binge eating often occurs at times of stress, anger, boredom, loneliness or distress, and is used as a way to cope with or distract from challenging emotions. A person’s feelings about their body, weight and shape can also trigger someone to binge eat. For example, someone might break a ‘diet rule’, they might feel full, or they may feel extremely hungry due to dieting.

To understand the binge-restriction cycle, see this diagram.

A person with bulimia nervosa can become stuck in a cycle of binge eating, followed by attempts to compensate for this, which can lead to feelings of shame, guilt and disgust. These behaviours and feelings can lead to an obsession with food and dieting and to body image disturbance.

People experiencing binge eating disorder and bulimia nervosa may be secretive about their eating habits and their eating disorder can remain undetected for a long time. They may also be unaware that evidence-based and evidence-informed treatments are available and accessible. If people are of higher weight they may encounter misdiagnoses in assessment, inappropriate treatment approach, and stigma from health professionals. People may present for weight-reduction assistance or be advised to lose weight before a diagnosis has been made. Health professionals providing support for people with higher weight should screen for eating disorders and be aware of the negative consequences of dieting and weight-reduction strategies.

(See NEDC fact sheets on binge eating disorder, bulimia nervosa, disordered eating and dieting, and our Eating disorders and people with higher weight page for more information.)

Among the complex environmental factors that influence the development or maintenance of binge eating disorder in adults are: weight/shape/size discrimination, racism, sexism, sociocultural ideals and messaging related to diet culture, health system barriers including cost, homelessness, unemployment, poverty and food insecurity; marginalization or under-representation of people with low socioeconomic status, people who are black, indigenous or people of colour (BIPOC), people who are LGBTIQA+; economic precarity and food insecurity, which can lead to a pattern of forced restriction and binge eating, predatory food industry practices; and stigma related to body weight/shape/size/mental health diagnosis, trauma and adversity. (Bray et al, 2022)

The numbers tell a story of their own.

Recent data (Tannous et al., 2021; State of Victoria, 2019; Phillipou et al, 2020; Miskovic-Wheatley et al 2022; NEDC, 2020; Victorian Agency for Health Information, 2022) indicates that eating disorder prevalence is likely to be considerably higher than the frequently cited statistic that eating disorders are experienced by 4% of the population (around one million Australians) (Butterfly Foundation, 2012). Of people with eating disorders, 47% have binge eating disorder (BED) compared to 12% with bulimia nervosa, 3% with anorexia nervosa, and 38% with other eating disorders (Butterfly Foundation, 2012). Of people with binge eating disorder, just over half (57%) are female (Hay et al., 2015), and recent data suggests that the prevalence of BED may be nearly as high in men as in women (Hay et al., 2015).

Among people with a diagnosable eating disorder, only around one in four access eating disorder treatment (Hart et al., 2011). Relatively few people who meet the diagnostic criteria for an eating disorder receive a diagnosis or evidence-based treatment, and there is often a long delay between the two, particularly for binge eating disorder and bulimia nervosa (Hamilton et al., 2022).

Some of the medical and psychological impacts and complications associated with binge eating disorder include cardiovascular disease, Type 2 diabetes, osteoarthritis, kidney failure, social isolation, self-harm or suicidality (Sheehan et al., 2015). Bulimia nervosa is the eighth leading cause of burden of disease and injury in females aged 15-24 in Australia. (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2019), and suicide is up to 7.5 times higher for someone with bulimia nervosa than the general population. (Preti et al., 2011).

It is time to tell a different story.

To build the system of care for people experiencing eating disorders, we must identify groups being missed, learn why this is occurring, and find ways to reach these populations. Educating the community, health professionals, health services, and government agencies about binge eating disorder and bulimia nervosa and the serious medical and psychological complications that cause long-term impacts on people’s lives is vital. As a society, diet culture and weight stigma need to be addressed, and in health care, recognise that a weight-inclusive or weight-neutral stance can prevent harm.

We know eating disorders, including binge eating disorder and bulimia nervosa, can occur in people of any age, weight, size, shape, gender identity, sexuality, cultural background or socioeconomic group. Targeted studies of diverse groups are needed, including men, people with higher weight, older people, people from different demographic backgrounds, people with ARFID, neurodivergent groups, LGBTQIA+ communities, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and, specifically, people experiencing binge eating disorder and bulimia nervosa among these groups.

We will look at these issues from three sides: EDV presents a lived experience perspective, Western Sydney University researcher Dr Deb Mitchison an academic outlook, and Inside Out discusses how clinicians can adapt research to practice.

Q&A with Eating Disorders Victoria

“I was engaged in mental health services for a number of years for other things before my binge eating disorder was recognised. Not only did health professionals not know the signs or the questions to ask, neither did I. I had never heard of binge eating disorder before being diagnosed, I just thought the problem was me. Now I know that I had a legitimate, and treatable, eating disorder,” lived experience advocate Sarah Bryan.

Sarah Bryan led the working group on EDV’s Our Vision for BED. We spoke to EDV’S Communications Manager Breanna Guterres about the project.

Tell us about EDV’s ‘Our Vision for BED’ initiative. What are its key messages/main themes?

Our Vision for BED in Victoria is underpinned by four key themes:

1) Binge eating disorder is debilitating and life-limiting, and thus deserves equal recognition to other eating disorders;

2) People with binge eating disorder need non-discriminatory and weight neutral care;

3) Entry to care must be accessible to account for high levels of stigma that leads to shame;

4) Peer-led binge eating disorder initiatives are an essential adjunct to clinical treatment.

You can read more about this vision here. The vision and underpinning themes were devised by people with lived experience of binge eating disorder.

What was EDV’s community saying about binge eating disorder that made you see the need to start this work?

We were hearing from more and more Victorians living with binge eating disorder who felt like their experience was considered less important than other eating disorders. This is especially reflected in our public health system where treatment services are heavily skewed towards restrictive eating disorders and weight restoration. There are also continual themes of stigma and shame, which compounds these feelings and prevents people from engaging in the help they need. Our community experiencing binge eating disorder wants to experience accessible and respectful care, and they are entitled to that.

What roles did people with lived or living experience of binge eating disorder play in this initiative?

Lived experience was pivotal to this initiative. We started by contracting a lived experience coordinator for the project, Sarah Bryan, who is an advocate and mental health worker. We then went out to our community and sought expressions of interest for a focus group to determine the messaging. We ended up with six community representatives who shared their lived experience to help formulate the key messages of the campaign.

What did the volunteer working group hope that setting out this Vision would achieve?

The group were passionate about helping other people experiencing binge eating disorder to get the support they need. All group members were either recovered or going through recovery, so they know the benefit of being connected to health professionals and community supports. By sharing their lived experience through this initiative, they are helping build a better system of care for themselves but also for other Victorians who are yet to find this support.

How is it hoped that these measures will benefit people with lived and living experience?

We hope that by putting a specific focus on this issue that it will raise the profile of binge eating disorder among key stakeholders and decision makers. Currently, Victoria is undergoing mental health system reform and we are also developing a new statewide eating disorder strategy. We believe that this is the perfect opportunity to take action and ensure binge eating disorder support services are embedded in a reformed mental health system.

Read more about EDV's vision here.

Q&A with Western Sydney University researcher and clinical psychologist Dr Deb Mitchison

Tell us about your work in eating disorders and how you became involved in the field. What are your main aims in your role as a researcher?

In my role as a researcher my aims are to find ways to reduce the prevalence of eating disorders. To date this has primarily been through epidemiological research studies where I work alongside colleagues internationally to conduct and analyse the data from large surveys to shine a light on just how far-reaching eating disorders are, in terms of who experiences them and at what cost. This helps us to understand the magnitude of and targets for our task to prevent eating disorders. I also conduct longitudinal studies, which allow me to pinpoint specific external and internal factors that predict whether a person will develop (or not) or recover from (or not) an eating disorder over time. I am lucky - my work allows me to interact with passionate colleagues (both clinicians and researchers) and people with lived experience who I learn from every day.

How do stigma and other perceived barriers delay treatment seeking for people with binge eating disorder and bulimia nervosa and what measures could be taken to improve this?

Unfortunately, eating disorders are still largely misunderstood. One of the major misconceptions is that eating disorders are only experienced by young thin white girls. This stereotype exists within the general public, but sadly also among mental health experts. As a result, we have less research conducted on diagnoses other than anorexia nervosa, on genders other than female, on body shapes other than thin, and on ethnic and racial groups other than white/Caucasian.

This causes all sorts of blind spots among health professionals who are critical to identifying eating disorders and helping people seek appropriate treatment. But it also causes problems with self-identification – when one does not see themselves represented in the public and academic narrative of what an eating disorder is, then they will almost definitely struggle to identify an eating disorder within themselves.

In our research on this topic, we have found that only 10.1% of adolescents who met criteria for an eating disorder in a survey of 5000 school students who met criteria for an eating disorder had ever received treatment, and that significant factors related to whether treatment had been accessed include female gender, identifying as having an eating disorder (which was also related to being female), and having a more “recognisable” eating disorder (e.g., anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa) (Fatt et al., 2020, and Fatt et al., 2021).

Relatedly, we have also found that among people who recently commenced treatment in a specialist centre for an eating disorders, the lag between when a person first started experiencing symptoms to when they started treatment was significantly longer among people with a diagnosis of bulimia nervosa (8.4 years) or binge eating disorder (10.4 years), compared to people with anorexia nervosa (2.2 years), and this was despite comparable levels of eating disorder symptom severity (Hamilton, 2022).

Perhaps most worrying is that the treatment-seeking sample in this study was primarily comprised of people who meet the young white female stereotype, and so the statistics for boys/men, people of other ethnicities and older people with eating disorders is likely to indicate a much longer wait, if treatment is accessed at all.

What needs to happen to make a difference here is education of what eating disorders are and who experiences them, and this should be co-designed alongside people with lived experience who represent the true diversity of eating disorders. Who this education needs to target includes the general public, young people in school, and health professionals in training and in practice. How this education should be disseminated is through media campaigns; primary, secondary and tertiary curriculum redevelopment; and professional development packages. Then of course there is the need to test whether our current treatments actually perform well with diverse groups of patients and consider under what circumstances there may be a need to develop population-specific treatments.

The hidden burden of eating disorders: an extension of estimates from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019’ (Santomauro, et al. 2021) shone a light on the fact that binge eating disorder and OSFED were the most prevalent eating disorders globally, with 41.9 million cases, and their relative contribution to eating disorder prevalence increased with age. Given its importance, what should the research agenda be for binge eating disorder/and bulimia nervosa?

The reason this study was conducted in the first place is related to what we were talking about above regarding the lack of eating disorder knowledge – in this case we were seeking to correct under-estimations of eating disorder prevalence and associated disability due to a previous study having only included anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa in calculating global eating disorder burden. The findings were stark – four-times greater prevalence with twice the disability than previously documented when we include binge eating disorder and OSFED!

The extremely rigorous methodology employed in this study by the Global Burden of Disease authors who are seen as leaders in health statistics means that the statistics will hopefully be taken seriously, and that eating disorder burden cannot continue to be ignored by health researchers and funders. It provides a clear impetus to conduct research on the methods to reduce eating disorder burden. In my opinion some of the more obvious directions for future research would be partnering with government and independent school systems to implement and evaluate the effectiveness and mechanisms of rolling out prevention programs – whether this be standalone eating disorder programs or content integrated into existing mental health programs.

Research is also required to address barriers related to a lack of clinician knowledge/confidence in working with eating disorders – partnerships with the university sector should guide this work. A one-size-fits-all approach is unlikely to work for prevention or treatment, and I am pleased to see that as a field we are moving toward recognition of the need for an evidence-based understanding of how to predict who will benefit from what type of intervention, so that we can better utilize a “menu of options” to the benefit of people who suffer and their families.

Could you tell us about some of the findings from the study Twenty-year associations between disordered eating behaviors and sociodemographic features in a multiple cross-sectional sample (Santana, et al., 2022) about increases in binge eating. How can this research knowledge be interpreted in public health campaigns, and in the identification and clinical management of eating disorders?

In this study we found that binge eating prevalence in the general population of people aged > 15 years in South Australia has been steadily increasing over the 20-year period (1998 to 2017). Importantly, when we divided up the participants into various age groups, and by gender, geographic distance from cities, work status, marital status and education level we found the same effect - … (it) was on the rise in every sector of the population. In fact the only group where we did not see this was the small proportion of participants who were identified as underweight. What we did also find was that those who were the most likely to be reporting binge eating were younger, single and with a higher body mass index – but men and women were equally likely to endorse this behaviour.

These findings really further underscore the needs I have described above, for public health campaigns to re-educate everyone on who experiences disordered eating and what this looks like – perhaps with a bit more urgency giving the rising rates over time that this study found. One further point to make here is that people who are binge eating are likely to be living in larger bodies – this can cause blind spots for doctors who may find it difficult to look past their concerns about body weight to properly assess for disordered eating and refer to an eating disorder clinician when indicated. Dissemination of the NEDC's Management of eating disorders for people with higher weight: clinical practice guideline will be critical in overcoming this sticking point in healthcare.

Deb Mitchison is an NHMRC Research Fellow and a clinical psychologist, specialising in eating and body image disorders. Deb completed her training as a clinical psychologist in 2012 and received her PhD in Medicine in 2015. Following her PhD she commenced a Macquarie University Research Fellowship. In 2019 Deb moved back to WSU to commence an NHMRC (Health Professional) Early Career Fellowship. She has published over 100 peer-reviewed scientific articles and enjoys collaborating with many academics across Australia and the globe, supervising HDR students, and has also been an active member of the Australia and New Zealand Academy for Eating Disorders where she contributes to professional development and advocacy.

Q&A with Inside Out Institute for Eating Disorders’ Dr Jane Miskovic-Wheatley, Sarah Barakat and Emma Bryant

Your work on The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and associated public health response on people with eating disorder symptomatology: an Australian study (Miskovic-Wheatley et al., 2022) found a 66% increase in binge eating symptomatology. How can new research findings such as this be translated into work practices for clinicians that will benefit the growing number of people experiencing an eating disorder of this type?

Dr Jane Miskovic-Wheatley: We directly asked people about their symptoms as well as diagnostic profile as previous research had suggested that there is more eating disorder experience in the community than is diagnosed. This assertion was supported by our research that found 40.5% of participants had not sought formal diagnostic assessment and less than half were in treatment, yet the average Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire score was above the cut off used for Medicare Eating Disorder Plans, indicating a high level of symptomatology in the the community study group.

This research provides evidence that more people in the community may be experiencing symptoms yet are not seeking treatment, so we need to advocate for less stigma and more community awareness, more screening in primary care settings, more focus on clinical engagement and more provision of evidence-based treatment. With the Medicare Eating Disorder items there are more treatment options available, however challenges exist to accessing that care, such as difficulties meeting the health care plan requirements, long wait lists for clinicians, and shortage of clinicians in rural and regional areas. Developments such as InsideOut’s provision of workforce development and online training for clinicians, the ANZAED credentialing system, the Butterfly helpline, guidelines and resources provided by NEDC and Medicare telehealth items are excellent examples of the resources available to support clinicians to provide care for the growing number of people with a lived or living experience of eating disorders.

Despite the higher population prevalence of binge eating disorder and bulimia nervosa, why do you think they are under-represented and under-treated? What current tools can clinicians use to improve this?

Sarah Barakat: We know that very few patients with binge eating disorder present to treatment with binge eating as their primary concern. Rather, individuals will often present with non-specific symptoms related to anxiety and/or depression, or in some cases seeking weight loss treatment or advice. People commonly experience high levels of shame and embarrassment around the binge eating behaviours and can be reluctant to disclose them, or they may not understand that these behaviours are in fact symptoms of an eating disorder. Without adequate training, knowledge and understanding of these disordered eating behaviours and symptoms, health professionals may overlook signs of disordered eating or, if the person is in a larger body, be inclined to suggest weight loss strategies without an assessment of any underlying disordered eating symptoms.

That is why it’s important that as clinicians we are aware of any biases and stigma and healthcare professionals ask questions about eating behaviours regardless of the person’s age, weight, gender, cultural or financial background.

There are several validated screening tools that are available for clinicians to use. Some are specific to binge eating behaviours, such as the Binge Eating Disorder Screener (BEDS-7), which consists of seven questions specifically on symptoms of binge eating disorder. Others screen more broadly for symptoms across a range of eating disorders, such as the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q), which includes 28 questions. The InsideOut Screener (see below) is a great option as it is a six-question tool which also assesses a broad range of eating disorder symptoms and has been validated against the EDE-Q. It is also helpful to ask open-ended questions to people about their eating patterns throughout the day, then with some more focused questions around binge eating, such as “Do you ever find yourself eating a lot more than what you’d like?”, “At those times do you feel like you are out of control? As though you can’t stop eating?”, “What do you find yourself eating at those times?” and “How do you feel following?”.

Tell us about Inside Out Institute’s binge eating e-therapy program BEeT.

Sarah Barakat: Brief BEeT is a digital intervention based upon cognitive behavioural therapy (BEeT). BEeT is a program consisting of one-hour interactive multimedia sessions. It aims to decrease binge-eating episodes and compensatory behaviours by employing evidence-based behavioural techniques which work to establish structured, regular eating patterns and challenge fears about weight gain. People are supported through online sessions by a pre-recorded therapist, who explains the core therapeutic principles. Individuals can also access additional digital tools to facilitate self-monitoring of eating and associated behaviours all via their personal devices.

How important was the predominant use of behavioural interventions in this brief online program (i.e., food monitoring, regular eating, and weekly weighing)? What are the implications for a clinician working in this area?

Sarah Barakat: Data from two studies that we’ve conducted at InsideOut have shown that the behavioural strategies included in BEeT are instrumental in the treatment of binge eating. A brief version of BEeT (consisting of the first four sessions) was piloted in both a sample of people with bulimia nervosa (Barakat et al., 2017) and binge eating disorder (Rom et al., 2022). The brief intervention focused solely on food monitoring, regular eating and weekly weighing. Both studies found that the brief four-session intervention achieved a significant decrease in binge episodes and associated loss of control from pre- to post-treatment. Given that we know dropout is a common problem in eating disorder treatment, especially for online treatments, by moving towards briefer interventions with only the most potent strategies, means clinicians can maximise exposure to therapeutic content and treatment gains prior to disengagement.

How could a supported online therapy such as BEeT help clinicians work with people experiencing binge eating disorder or bulimia nervosa to reduce the consequences of long-term eating disorder behaviours?

Sarah Barakat: BEeT offers scope for both self-directed and blended treatment options. Clinicians in the community can refer people to complete BEeT and know that the person is getting access to high quality, evidence-based care. With mental health services overwhelmed by demand following the COVID-19 pandemic, online tools such as BEeT represent an invaluable way to reduce waiting times and lessen pressure on clinicians without compromising care. This is a particularly valuable opportunity for clinicians who are being trained in eating disorder-specific treatments as it provides the option for people to receive specialised treatment of binge eating and frees up more time for the clinician to provide support for any comorbid mental health concerns in therapy sessions.

Brief BEeT and 10-session BEeT delivered as an independent pure self help treatment will be available to the public before Christmas 2022. Keep an eye on InsideOut's website for the release date.

Tell us about the Inside Out Screener (IOI-S).

Emma Bryant: The IOI-S is a brief, six-item screening tool co-designed and validated for online use (and currently being validated in headspace settings and GP clinics around Australia for face-to-face use). It assesses eating disorder risk and symptomatology using sensitive, non-confrontational language, understanding that approaching these issues and seeking help can be very daunting for many people. The screener is designed for people to access in their own time, in the privacy of their own home, to see if they might need to seek help – and to gently encourage them to do so.

Research shows the first place many people seek healthcare information is online, and we know that early identification/intervention drastically improves prognosis in all eating disorders, so we're trying to get to people early in the illness course. The six questions of the screener cover known facets of eating disorder pathology and were co-designed with individuals with lived experience so that they reflect the experience or presentation of early symptomatology and are easily comprehensible.

How could a digital tool such as the Inside Out Screener help clinicians identify the symptoms of binge eating disorder and bulimia nervosa in people from various demographic and sociocultural groups?

Emma Bryant: The IOI-S is designed to capture a range of eating disorder symptomatology including binge eating and compensatory behaviour. Because the questions are quite broad the screener is sensitive to a range of manifestations of behaviour, which may vary by culture and/or demographic. Additionally, being a free, online resource, it can be accessed by anyone anywhere, encouraging people who may otherwise not seek help due to lack of appropriate services or stigma/shame (the latter of which is a significant barrier in some cultures) to do so. Individuals can print out their results and take them to a primary care physician - the screener also links to our treatment services database available on the InsideOut website, which lists eating disorder specialists (including dietitians, social workers, psychologists, etc.) by region.

What can clinicians learn from your research findings? What are some take-homes for them so they can better screen for binge eating disorder and bulimia nervosa?

Emma Bryant: In our validation study (Bryant et al., 2021) with a community sample of 1346 people aged 14-74, almost 1 in 10 people met diagnostic criteria for binge eating disorder. This is obviously a significant number of people, suggesting screening for this condition - which has serious impacts on health and quality of life - is very important.

Anyone struggling with disordered eating, or an eating disorder deserves help and should be offered so at the earliest possible opportunity. There is no shame in dealing with these kinds of problems - it is very common and usually a coping mechanism for something else going on in a person's life. Using the language that is adopted by the IOI-S is encouraged - asking a person how they feel about their relationship with food, whether they feel distressed, what can you do to help, etc. - in a non-judgmental way, is exceptionally important. And although physical symptoms (including weight) are important, this should not be the focus and is not an indication of a person's health or eating disorder status.

Dr Jane Miskovic-Wheatley (BSc, Psych Hons 1, MSc, DCP) is a clinical psychologist and researcher with over 20 years’ experience working across several different research projects and sites, all focused on improving the lives of people with a lived or living experience of eating disorders. She is the Research & Translation Lead for the InsideOut Institute, University of Sydney, leading or contributing to over 20 innovative research projects.

Sarah Barakat (B.Psych (Hons I), M.ClinPsych) is a University of Sydney PhD Candidate conducting her research with InsideOut Institute. Sarah is coordinating a multisite, randomised controlled trial which aims to investigate the effectiveness of an online self-help treatment program titled Binge Eating eTherapy (BEeT). She is also a psychologist.

Emma Bryant is a researcher and PhD candidate at InsideOut. She holds a Bachelor of Psychological Science (Deakin University), a Bachelor of Medical Science (Hons I) (USYD), and won first place in both the ANZAED/AED Early Career Travel Scholarship and the Peter Beumont Young Investigator Award in 2021 and is a holder of the University of Sydney James King of Irrawang PhD Travelling Scholarship.

Guide to binge eating disorder and bulimia nervosa treatment options

Access to evidence-based treatment has been shown to reduce the severity, duration and impact of binge eating disorder and bulimia nervosa. Research indicates that several psychological therapies are effective in the treatment of binge eating disorder and bulimia nervosa. These include:

Binge eating disorder:

For adolescents and adults, treatment models include Cognitive Behaviour Therapy Enhanced (CBT-E), Cognitive Behaviour Therapy – Guided Self Help (CBT-GSH) and Interpersonal Therapy (IPT).

Bulimia nervosa:

For children and adolescents, treatment models include eating disorder-focused CBT (CBT-ED) with family involvement and Bulimia nervosa-focused family therapy.

For adults, treatment models include Guided self-help CBT-ED, CBT-ED, and IPT.

Psychological therapies are shown to have the greatest impact on eating disorder symptom reduction and other outcomes. Current evidence suggests that psychiatric medications should not be offered as the sole treatment for any eating disorder. Medication may be indicated as an adjunct to psychological therapy where there is a co-occurring mental health condition.

Learn more about Treatment Options here.

NEDC notes the emerging evidence and strong lived experience perspectives that cognitive behavioural approaches may not fit for all people experiencing an eating disorder. We encourage clinicians to take a person-centred approach that considers gender, neurology, cultural background and other important aspects of the person’s experience alongside evidence-based or evidence-informed practice.

New resources

Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD) is a complex mental health condition, classified not as an eating disorder but within the obsessive-compulsive and related disorders in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). BDD is characterised by excessive appearance-related preoccupations, repetitive compensatory behaviours and causes clinically significant distress or impairment daily activities. Our new Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD) fact sheet discusses characteristics, warning signs, impacts and complications, causes and risk factors, treatment options and recovery.

The Quick Reference Guide for Primary Care Professionals and Service Providers has been compiled to assist service providers and Primary Health Networks develop evidence-based policies, procedures and plans for service development and delivery, and also help GPs, health and other professionals support patients, clients, students and their families.

Dieting is not a normal part of life, families are not to blame, eating disorders are not a lifestyle choice or a cry for attention, and can affect anyone. Our Myths infographic explains the truth behind five common misconceptions about eating disorders.

Our updated Eating disorders: Identification and response fact sheet provides information about the different types of eating disorders, screening tools that can be used by health professionals to detect the possibility of an eating disorder and identify when a comprehensive assessment is warranted, and a list of warning signs and responses.

We’ve also updated our Cognitive Behavioural Therapy Guided Self Help (CBT-GSH) fact sheet, designed for GPs and health professionals who are seeking a better understanding of CBT-GSH in eating disorders, and their role in using this as a treatment in some eating disorder presentations.

Browse NEDC Resources here, including fact sheets, infographics and booklets.

Upcoming training and events

NOVEMBER

8, 9 Nov Training: The Victorian Centre of Excellence in Eating Disorders (CEED), Family-Based Treatment for Adolescents with Anorexia Nervosa

10 Nov Webinar: Families Empowered And Supporting Treatment for Eating Disorders (F.E.A.S.T.), Guided self-help family-based treatment for adolescents with anorexia nervosa: what is it and who is it for

16 Nov Event: Eating Disorders Neurodiversity Australia (EDNA) Chair Laurence Cobbaert will be presenting on the topic of Autism and Eating Disorders at Autism & Making Space, an online event hosted by the Honourable Emily Bourke, South Australian Assistant Minister for Autism

16 Nov Webinar: Butterfly, Body Image Training for Educators

17 Nov Webinar: Butterfly, Understanding Eating Disorders in Young People

17 Nov Webinar: Eating Disorders Families Australia (EDFA), Parenting and Setting Boundaries around an Eating Disorder

17, 18, 19 Nov Training: Eating Disorders Training Australia, Assessment and treatment of adolescents and adults with Eating Disorders in private practice: A comprehensive introductory 3-day workshop (Intro + CBT-E)

23, 24, 30 Nov and 1 Dec Training: The Victorian Centre of Excellence in Eating Disorders (CEED), CBT-E Cognitive Behaviour Therapy for Eating Disorders

25 and 26 Nov Workshop: BodyMatters, Maudsley Family Therapy

DECEMBER

1 Dec Workshop: Western Australia Eating Disorders Outreach and Consultation Service (WAEDOCS), Understanding the Complexities & Management of Binge Eating Disorder (BED) & Implementing a Health at Every Size® Framework for Dietetic Practice

1 Dec Webinar: EDFA, Professor Janet Treasure – How to support your loved one through an eating disorder

Click here to access these and other upcoming events.

Click here to submit your own event.

References and further reading

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australian Burden of Disease Study: impact and causes of illness and death in Australia 2015. Canberra; 2019.

Barakat, S., Maguire, S., Surgenor, L., Donnelly, B., Miceska, B., Fromholtz, K., ... & Touyz, S. (2017). The role of regular eating and self-monitoring in the treatment of bulimia nervosa: a pilot study of an online guided self-help CBT program. Behavioral Sciences, 7(3), 39.

Bray, B., Bray, C., Bradley, R., & Zwickey, H. (2022). Binge Eating Disorder Is a Social Justice Issue: A Cross-Sectional Mixed-Methods Study of Binge Eating Disorder Experts’ Opinions. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(10), 6243.

Bryant, E., Miskovic-Wheatley, J., Touyz, S. W., Crosby, R. D., Koreshe, E., & Maguire, S. (2021). Identification of high risk and early stage eating disorders: first validation of a digital screening tool. Journal of eating disorders, 9(1), 1-10.

Butterfly Foundation. Paying the price: The economic and social impact of eating disorders in Australia. Australia: Deloitte Access Economics; 2012

Fatt, S. J., Mond, J., Bussey, K., Griffiths, S., Murray, S. B., Lonergan, A., ... & Mitchison, D. (2020). Help-seeking for body image problems among adolescents with eating disorders: findings from the EveryBODY study. Eating and Weight Disorders-Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity, 25(5), 1267-1275.

Fatt, S. J., Mond, J., Bussey, K., Griffiths, S., Murray, S. B., Lonergan, A., ... & Mitchison, D. (2021). Seeing yourself clearly: Self‐identification of a body image problem in adolescents with an eating disorder. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 15(3), 577-584.

Hamilton, A., Mitchison, D., Basten, C., Byrne, S., Goldstein, M., Hay, P., ... & Touyz, S. (2022). Understanding treatment delay: perceived barriers preventing treatment-seeking for eating disorders. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 56(3), 248-259.

Hart LM, Granillo MT, Jorm AF, Paxton SJ. Unmet need for treatment in the eating disorders: a systematic review of eating disorder specific treatment seeking among community cases. Clin Psychol Rev. 2011;31(5):727-35.

Hay P, Girosi F, Mond J. Prevalence and sociodemographic correlates of DSM-5 eating disorders in the Australian population. J Eat Disord. 2015;3(1):1-7.

McLean, C., Utpala, R., & Sharp, G. (2021). The impacts of COVID-19 on eating disorders and disordered eating: A mixed studies systematic review and implications for healthcare professionals, carers, and self.

Miskovic-Wheatley, J., Koreshe, E., Kim, M., Simeone, R., & Maguire, S. (2022). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and associated public health response on people with eating disorder symptomatology: an Australian study. Journal of eating disorders, 10(1), 1-14.

Mulders-Jones, B., Mitchison, D., Girosi, F., & Hay, P. (2017). Socioeconomic correlates of eating disorder symptoms in an Australian population-based sample. PLoS ONE, 12(1), e0170603.

National Eating Disorders Collaboration (NEDC). Eating disorders in the time of COVID: A snapshot of Australian treatment services. NEDC; 2020.

Phillipou A, Meyer D, Neill E, Tan EJ, Toh WL, Van Rheenen TE, Rossell SL. Eating and exercise behaviors in eating disorders and the general population during the COVID‐19 pandemic in Australia: Initial results from the COLLATE project. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2020;53(7):1158-65. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23317

Preti A, Rocchi MBL, Sisti D, Camboni M, Miotto P. A comprehensive meta‐analysis of the risk of suicide in eating disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2011;124(1):6-17.

Rom, S., Miskovic‐Wheatley, J., Barakat, S., Aouad, P., Fuller‐Tyszkiewicz, M., & Maguire, S. (2022). Evaluating the feasibility and potential efficacy of a brief eTherapy for binge‐eating disorder: A pilot study. International Journal of Eating Disorders.

Santomauro, D. F., Melen, S., Mitchison, D., Vos, T., Whiteford, H., & Ferrari, A. J. (2021). The hidden burden of eating disorders: an extension of estimates from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet Psychiatry, 8(4), 320-328.

Sheehan DV, Herman BK. The psychological and medical factors associated with untreated binge eating disorder. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2015;17(2).

State of Victoria. Royal Commission into Victoria’s Mental Health System, Interim Report, Parl Paper No. 87 (2018–19). [Internet]: State of Victoria; 2019. Available from: https://finalreport.rcvmhs.vic.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/RCVMHS_InterimReport.pdf

Tannous WK, Hay P, Girosi F, Heriseanu AI, Ahmed MU, Touyz S. The economic cost of bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder: a population-based study. Psychological Medicine. 2021:1-5. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291721000775

Victorian Agency for Health Information (VAHI). Mental health, alcohol and other drug treatment services in Victoria - August 2022. [Internet]. State of Victoria; 2022. Available from: https://vahi.vic.gov.au/publications?field_publication_report_target_id=8821